The French myth of secularism

Mayanthi Fernando, University of California, Santa Cruz

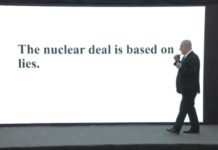

Commentators in France and elsewhere have taken the recent terrorist attacks in Paris as an occasion to reflect more broadly about Muslims in France. Many read the attacks as a sign of French Muslims’ refusal to integrate. They’ve asked whether Muslims can be fully secular and expressed doubt as whether one can be both Muslim and French.

Even as we try to make sense of what happened, however, we should be wary of myths about French secularism (laïcité) and French citizenship being spun in the aftermath of the attacks.

France understands itself and is often accepted as a preeminent secular nation that fully separates church and state and restricts religion to the private sphere.

The reality is more complicated, as more than 10 years of research on this issue have taught me.

In 1905, a major law officially separated church and state in France, though it did not go into effect in the northeastern region of Alsace-Moselle, which was under Prussian rule at the time. Even when Alsace-Moselle was reintegrated into France, however, it remained exempt from the 1905 law, and Catholicism, Calvinism, Lutheranism, and Judaism are still officially recognized religions in the region. As a result, religious education in one of those religions is obligatory for public-school students and the regional government pays the salaries of clergy of the four recognized religions.

Other exceptions to the separation of church and state

The 1905 law itself contains a number of exceptions.

For instance, though it forbids government financing of new religious buildings, it allows the government to pay maintenance costs for religious edifices built before 1905 – most of them Catholic churches. Thanks to later laws, the state also subsidizes private religious schools, most of them Catholic, some of them Jewish. And there exist other traces of Catholicism within the education system, like a public school calendar organized around Catholic holy days and public school cafeterias that serve fish on Fridays.

However, when Muslim French request the kind of accommodations offered to other religious communities in France, for example, state-funded Muslim schools, a school calendar that incorporates Muslim holy days, and the official recognition of Islam in Alsace-Moselle, they are reminded that France is a secular country where proper citizenship requires separating religion from public life.

Muslim appeals for religious accommodation are claims to civic equality within the existing parameters of laïcité. Yet those appeals paradoxically become the basis for questioning Muslims’ fitness as proper French citizens, by both right-leaning French Catholics and left-leaning French secularists.

Discrimination against Muslims

French Muslims are also caught in the contradictions of the French model of citizenship. The French state ostensibly recognizes individuals as individuals rather than as members of a community, but it also consistently discriminates against minorities. Because France refuses to recognize communal identities, however, it is difficult to voice claims of discrimination based on communal belonging. For example, because citizens are supposed to forgo particular racial, cultural, and religious attachments in lieu of a French national identity, the state refuses to collect census data about racial or religious belonging. This makes it hard to gauge racial and other disparities in government, higher education, and the workplace.

Yet social science research shows that nonwhite immigrants and their descendants as a group suffer systematic discrimination on the basis of their race, culture, and religion.

Indeed, race and religion come together in the term “Muslim,” used to identify a population of North and West African descent whose members a few decades earlier were referred to as immigrants and foreigners, or with terms that marked their ethnicity (e.g. Arabs). Muslim citizens and residents suffer disproportionately high levels of unemployment and face discrimination in the hiring process. CVs with Muslim-sounding names are often rejected on that basis alone, and Muslims are disproportionately imprisoned, due in part to racial profiling and differential treatment in the criminal justice system. Muslim children attend overcrowded, underfunded public schools.

Moreover, in recent years, the public practice of Islam has become increasingly difficult: a 2004 law bans the wearing of headscarves in public school and a 2010 law bans the face veils in all public spaces. Veiled women have been refused entry to university classes, banks, and doctors’ offices.

Neutral laws that are not neutral

However, because the republican model of citizenship refuses to recognize communal claims, anyone claiming to be the target of anti-Muslim discrimination only reinforces their communal difference from self- described “native” French. Moreover, much discriminatory legislation, including the two veil laws, is couched in neutral terms even as it clearly targets certain Islamic practices. The 2004 law against headscarves, for instance, bans “conspicuous religious signs” and the 2010 law against face-veils bans “the dissimulation of the face.” When Muslim French call attention to this problem, they are met with charges of communautarisme, of thinking and talking too much as Muslims rather than as French citizens. Not surprisingly, the Collective Against Islamophobia in France (CCIF) is often accused of “communalism.”

Even when Muslims make explicit claims to being French – and the vast majority does – those claims are rejected. In a telling incident, the Paris transit authority in 2012 refused to display an advertisement by the CCIF because of its “religious character” and “political demands.” The ad, part of the CCIF’s “We too are the nation” (Nous assusi sommes la nation) campaign, reimagined the painter David’s French Revolution-era “Tennis Court Oath” in the present, with veiled women, Arab men in hoodies, and visibly orthodox Jews, among other citizens, holding aloft French flags and copies of the oath pledging revolutionary ideals. The CCIF thereby affirmed their commitment to France, symbolically inscribing themselves into the French nation as original citoyens.

Rather than stemming from Muslims’ rejection of Frenchness, then, the supposed impossibility of being a Muslim and being a French citizen is largely generated by the contradictions of French secularism and French citizenship and by the majority’s inability to conceive of Muslims as French.

We should not deny the horror of January 6. But, in its aftermath, rather than uncritically reaffirm French national identity and wring our hands about Muslims’ refusal to integrate, we should use this moment of reflection to understand the various ways in which Muslims are consistently excluded from the nation, and to reassess the narrow bases of what it means to be French. ![]()

Mayanthi Fernando, Associate Professor, Anthropology, University of California, Santa Cruz

This article was republished on The Mecca Post with permission from The Conversation. The original article is here .